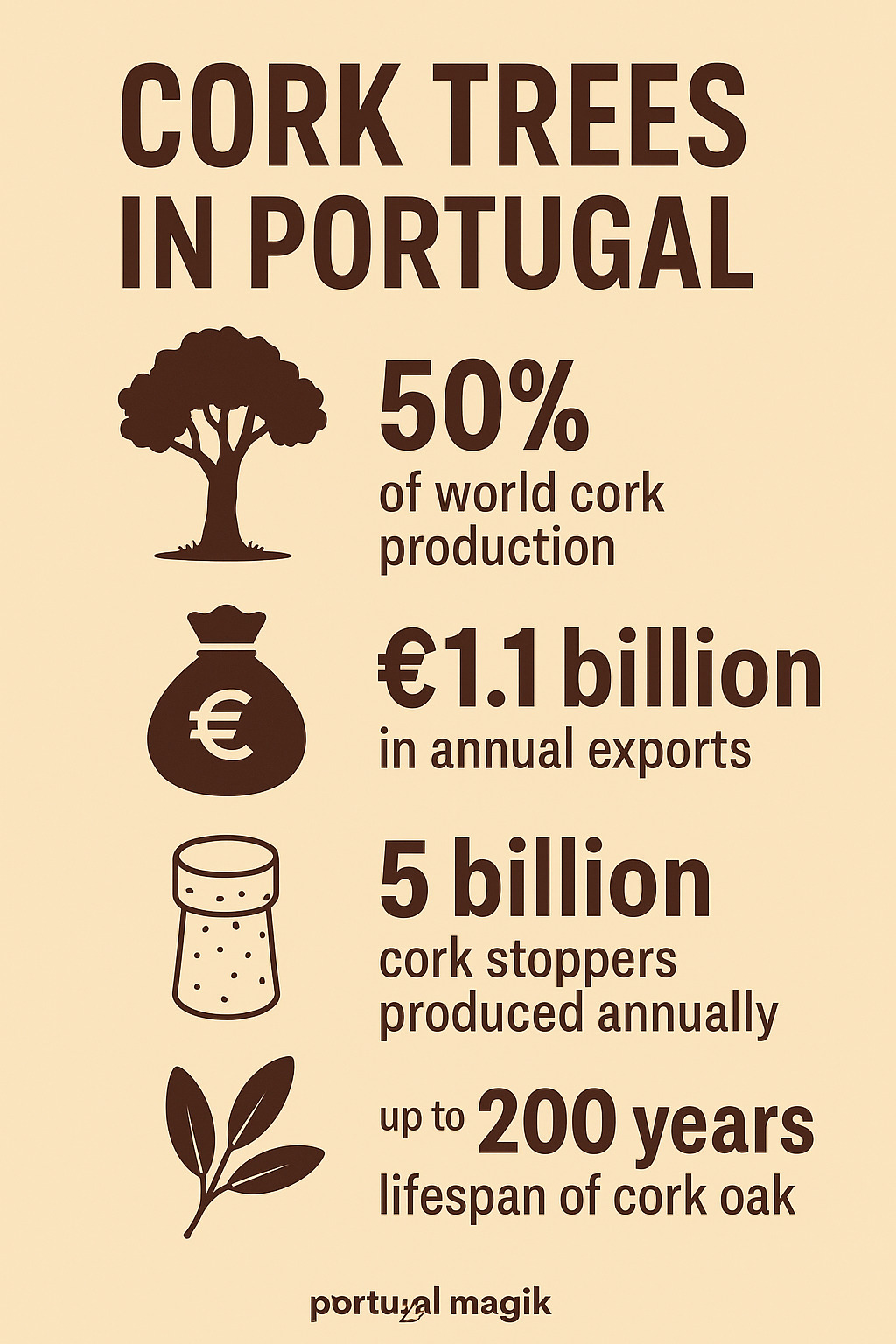

Cork trees are not just part of the landscape in Portugal — they are central to its economy, ecology, and cultural identity. These resilient trees, known scientifically as Quercus suber, are native to the western Mediterranean and thrive in the unique conditions of southern Portugal. They grow slowly but live long, with lifespans that can exceed 200 years. Over that time, they yield one of nature’s most versatile materials: cork.

Today, Portugal is the global leader in cork production, responsible for nearly 50% of the world’s supply. The cork oak tree is so important that it’s legally protected by the Portuguese government, and its bark is harvested under strict regulation. But there’s more to the story than just wine stoppers. Cork trees are woven into the environmental and economic fabric of the country — and their future is tied to how Portugal manages change.

What Is a Cork Tree?

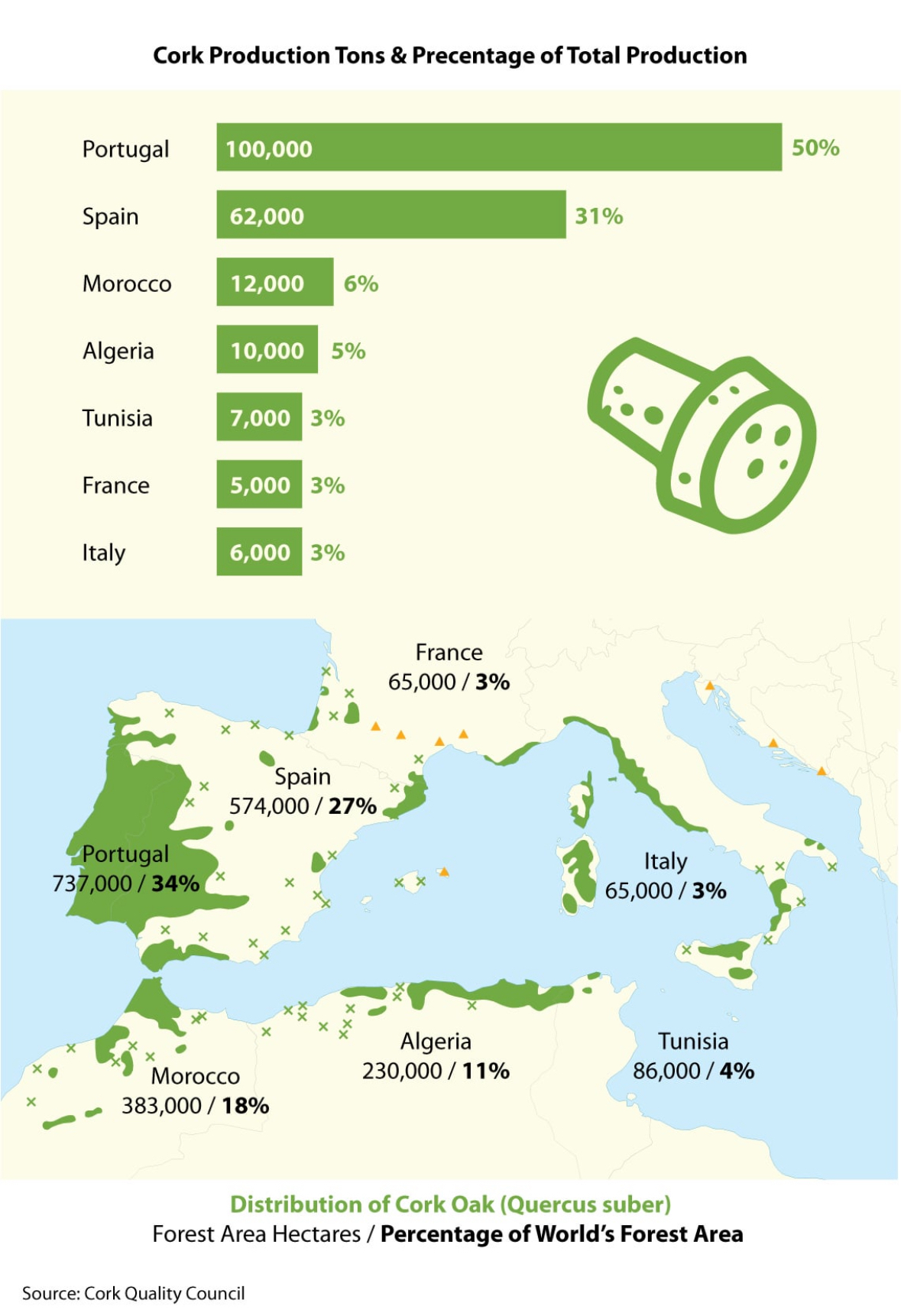

The cork oak is a medium-sized evergreen tree that grows mainly in Portugal, Spain, Algeria, Morocco, and parts of France and Italy. But Portugal stands apart for how well the tree adapts to its soils and climate — especially in the Alentejo region, which produces the bulk of the country’s cork.

Cork is not the wood of the tree, but its bark — a spongy, buoyant material that protects the tree from fire, pests, and dehydration. What makes cork unique is that it regenerates. Every nine to twelve years, the bark can be stripped without harming the tree. The first harvest comes when the tree is around 25 years old, but that early cork — called virgin cork — isn’t usable for high-quality products. It’s only after the third harvest (usually when the tree is 43 or older) that the bark is good enough for wine corks.

Portugal’s Cork Economy

Cork has been used for centuries in the Mediterranean, dating back to Ancient Greece. But it was in the 18th and 19th centuries that cork production in Portugal scaled up dramatically, driven by demand from the wine industry.

Today, Portugal’s cork sector is a €1.1 billion industry, employing over 20,000 people directly and many more indirectly. The country exports cork to more than 130 countries, with major markets including France, the U.S., Italy, Germany, and Spain. The iconic wine stopper is still the dominant product — making up about 70% of the industry’s value — but cork’s applications are diversifying fast.

Cork is now used in everything from flooring and insulation to fashion accessories, automotive parts, aerospace materials, and even surfboards. Its properties — lightweight, water-resistant, insulating, elastic, and biodegradable — make it a natural fit in industries looking to cut plastic or reduce environmental impact.

\

Cork Harvesting: A Skilled Art

Harvesting cork is not a casual job. It requires trained professionals known as tiradores. Using specialized axes, they strip off large sheets of bark with careful precision, making sure not to damage the delicate inner layers of the tree. The work is physically demanding and only done during the summer months, when the bark separates most easily from the trunk.

After the bark is removed, it’s left to dry in open air for six months before being boiled, flattened, and processed. Top-grade cork is punched into stoppers; lower grades are ground into granules and pressed into boards or composites.

The entire process is sustainable by design. Trees are never cut down for their bark, and a well-managed cork oak can be harvested over a dozen times in its life. That makes the cork industry one of the rare sectors where commercial use actually incentivizes forest preservation.

The Montado Ecosystem

Cork trees in Portugal don’t grow in dense forests but in savanna-like woodlands called montados. These mixed-use landscapes blend agriculture, grazing, and forestry in a balanced system that supports both biodiversity and rural economies.

Montados are among the richest ecosystems in Europe, home to hundreds of species, including endangered ones like the Iberian lynx and imperial eagle. They also play a major role in climate regulation. Cork oaks capture and store carbon, help retain groundwater, and prevent desertification — a growing risk in southern Europe as the climate changes.

But montados are under threat. Urban sprawl, intensive farming, and land abandonment are taking a toll. And climate change is adding stress through prolonged droughts, rising temperatures, and increased wildfires. Maintaining this delicate ecosystem will require coordinated action — from farmers, conservationists, and policymakers alike.

Cork in Portuguese Culture

The cork tree holds a special place in Portugal’s national consciousness. It’s not just a resource; it’s a symbol. In 2011, the cork oak was officially declared the national tree of Portugal, and its legal protections are some of the strictest in the world.

Cutting down a cork oak without government permission is illegal and punishable by fines. Farmers receive subsidies to maintain cork woodlands, and reforestation efforts are ongoing. In recent years, the government and NGOs have launched educational campaigns to promote cork as a sustainable alternative to plastics and synthetic materials.

Cork is also deeply tied to Portuguese design and identity. From minimalist cork handbags and shoes to architectural panels and furniture, designers are reimagining this humble material in modern, creative ways. It has become a symbol of Portuguese craftsmanship — rooted in tradition but open to innovation.

A Material for the Future?

The global market is shifting, and cork is finding new relevance. As sustainability moves from buzzword to business imperative, industries are turning to materials like cork that offer low environmental impact without sacrificing performance.

Major fashion brands like Louboutin, Stella McCartney, and Nike have incorporated cork into their products. Architects and interior designers prize cork for its acoustic, thermal, and aesthetic qualities. Even NASA has used cork composites for heat shielding.

At the same time, the wine industry — once seen as vulnerable to synthetic alternatives — has largely reaffirmed its commitment to natural cork. Studies show that wine sealed with natural cork ages better and is more valued by consumers. In response, cork manufacturers have improved quality control, introduced traceability technologies, and developed micro-agglomerated corks that combine performance and sustainability.

Challenges and Risks

Despite its strengths, the cork industry faces challenges. Climate change is the biggest long-term threat. Cork oaks are drought-resistant, but even they have limits. Warmer, drier conditions stress the trees, reduce bark quality, and make woodlands more vulnerable to fire and pests.

There are also economic risks. Cork production is slow, and the industry has high labor costs. Competing materials — like plastic or aluminum — are cheaper and easier to scale, even if they’re less sustainable. That means cork must keep proving its value in both quality and ecological terms.

Land use is another concern. As Portugal’s economy diversifies, rural areas are seeing shifts in ownership, purpose, and investment. Some farmers are switching to crops with quicker returns. Others are aging without heirs willing to maintain the traditional montado lifestyle. Without intervention, parts of the cork landscape could be lost.

The Path Ahead

Preserving Portugal’s cork heritage means more than saving a tree — it means protecting a whole way of life. Fortunately, many stakeholders recognize the stakes.

Government support remains strong. EU agricultural subsidies prioritize sustainable forestry, and national programs encourage reforestation and ecological land use. Scientific research is improving cork yield, tree resilience, and harvesting efficiency. And public awareness is growing, both within Portugal and globally.

The next chapter for cork in Portugal is not about nostalgia — it’s about adaptation. Cork’s future lies in diversification, sustainability, and storytelling. It’s a product that fits the needs of the 21st century — renewable, natural, and biodegradable. But to succeed, cork must keep evolving.

🌍 Global Cork Production: Share by Country

-

Portugal: ~50–60% of global output

-

Spain: ~25–30%

-

Morocco: ~5–6%

-

Algeria: ~5%

-

Tunisia, Italy, France: each ~1–3%

These figures confirm Portugal’s position as the world’s dominant cork producer

Conclusion

Cork trees are more than just producers of bark. In Portugal, they represent a model of how humans and nature can coexist productively over centuries. The cork industry shows that environmental protection and economic value don’t have to be opposites — they can reinforce each other.

If managed wisely, Portugal’s cork forests can continue to thrive — providing income, storing carbon, protecting biodiversity, and symbolizing a country’s commitment to living in balance with its land.